Vowels, Vowel Formants and Vowel Modification

VOWELS

The term 'vowel' is commonly used to mean both vowel sounds and the written symbols that represent them.

In phonetics, a vowel (from the Latin word 'vocalis', meaning 'uttering voice' or 'speaking') is a sound in spoken language that is characterized by an open configuration of the vocal tract, in contrast to consonants, which are characterized by a constriction or closure at one or more points along the vocal tract. Vowels are understood to be syllabic, meaning that they usually form the peak or nucleus (the central part) of a syllable - whereas consonants form the onset (any consonant or sequence of consonants preceding the nucleus) and coda (any consonant or sequence of consonants following the nucleus).

Vowels are extremely important to singing. They almost always carry the greatest energy in the speech signal because, during vowel phonation, the vocal tract is most open. Vowels are also stable segments of speech during which the articulators do not move, allowing the resonance frequencies of the vocal tract to remain more stable (minus the characteristic waxing and waning of the frequencies due to the rapid and periodic opening and closing of the vocal folds during phonation). Because of these characteristics, vowels are probably the easiest speech category to recognize in a spectrogram - an electronic device that mesures peaks in the harmonic spectrum of the voice during singing. A singer needs to learn to sing vowels while not allowing consonants, which resonate and 'project' more poorly than vowels do, to get in the way.

The different ways in which the vibrations and tension in the larynx affect the quality of a vowel are called phonation. The simplest phonation is called voicing. Voice or voicing is a term used in phonetics and phonology to characterize speech sounds, with sounds described as either voiced or voiceless (or unvoiced). A voiced sound is one in which the vocal folds, which are cartilages inside the larynx, vibrate during the articulation of the vowel. At the articulatory level, a voiceless sound is one in which the folds do not vibrate in order to produce the sound. (Voicing is the difference between the pairs of sounds that are associated with the English letters 's' and 'z', with the 'z' sound being voiced.) In all languages, without exception, most vowels are voiced sounds. (Most languages, in fact, have only voiced vowels.) In whispered speech, vowels are devoiced.

In both singing and speech, optimal vowel phonemes are voiced, and are tense and therefore particularly distinct. Optimal consonants, on the other hand, are voiceless and lax.

(Oral) vowels are formed with no major obstacles in the vocal tract so that there is no build-up of air pressure at any point above the glottis (the supra-glottal spaces). The air stream, once out of the glottis, passes through the speech organs and is not cut off or constricted by the supra-glottal resonators, nor by the articulators themselves, which means that they are 'open' sounds. The resonators, then, cause only resonance, reinforcing certain frequency ranges.

This isn't the case with consonants and nasal sounds, however. With consonants, there is a constriction or closure at some point along the vocal tract. For consonants, there are also antiresonances in the vocal tract at one or more frequencies due to oral constrictions. An antiresonance is the opposite of a resonance, such that the impedance is relatively high rather than low. Consequently, consonants attenuate or eliminate formants at or near these frequencies, so that they appear weakened or are missing altogether when looking at spectrograms. For these reasons, singers need to sing on open vowels, and not sustain consonant sounds, if they wish to maximize the resonance and carrying power of their voices.

In addition, for nasal consonants and nasal vowels, the vocal tract divides into a nasal branch and an oral branch, and interference between these branches produces more antiresonances. Furthermore, nasal consonants and nasal vowels can exhibit additional formants, called nasal formants, arising from resonance within the nasal branch. Consequently, nasal vowels may show one or more additional formants due to nasal resonance, while one or more oral formants may be weakened or missing due to nasal antiresonance. For these reasons, singers should avoid singing with excessive nasality in their tones, even when singing in a foreign language that utilizes nasal vowels, if they hope to achieve a more fully resonant sound.

There are three possible resonators involved in the articulation of a vowel: the oral cavity, the labial cavity, and the nasal cavity. The number of resonators involved distinguish between the type of vowels created. With oral vowels, there is no nasal resonance, as the soft palate is raised and air does not enter the nasal cavity. With nasal vowels, the nasal resonator is activated by lowering the soft palate and allowing air to pass through the nose and mouth simultaneously. In rounded vowels, a third resonator - the labial resonator - is activated from oral vowels when the lips are pushed forward and rounded. If, on the other hand, the lips are spread sideways or pressed against the teeth, as in the case of unrounded vowels, no labial resonator is formed.

A vowel's timbre (or colour or quality) depends on the number of active resonators (among the oral, labial and nasal cavities), the shape of the oral cavity and the size of the oral cavity. The articulators, primarily the tongue and lips, shape the vocal tract into these different resonating cavities, giving a characteristic acoustic quality to each vowel.

The shape of the oral cavity is determined by the general position of the tongue in the mouth. Based on positioning of the tongue, the vowels are divided into three classes: front, back and central vowels. In front vowels, the tongue body is held in the pre-palatal region. In back vowels, the tongue body is held in the post-palatal or velar region. In central vowels, the tongue body is in the medio-palatal region.

The size of the oral cavity is the last factor considered in the articulatory classification of a vowel. The size of the oral cavity depends directly upon the degree of aperture (opening) of the mouth ; that is, upon the distance between the hard palate (roof of the mouth) and the tongue's highest point. Arbitrarily, four degrees of aperture are distinguished, from the most closed (first degree) to the most open (fourth degree).

I will describe these features in greater detail in the section on Cardinal Vowels.

IPA SYMBOLS FOR VOWELS

Before continuing with this discussion on singing vowels, I would like to take some time to explain the symbols that I use for the spoken vowel sounds, which are those used internationally to represent the same sounds in language.

The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) is a system of phonetic notation, originally developed in 1886 by a group of French and British language teachers that later became known as the International Phonetic Association, that is used as a standardized representation of the sounds of spoken language. In 1888, the alphabet was revised so as to be uniform across languages, thus providing the base for all future revisions.

The IPA is used by foreign language students and teachers, linguists, speech pathologists and therapists, singers, actors, lexicographers, and translators. IPA symbols are used in phonetic transcriptions in modern dictionaries. More relevant to singers, IPA also has widespread use among classical singers for preparation, especially among English-speaking singers who rarely sing in their native language. In fact, opera librettos are authoritatively transcribed in IPA.

The Association created the IPA so that the sound values of most vowels and consonants taken from the Latin alphabet would correspond to 'international usage'. For this reason, most symbols are either Latin or Greek letters, or modifications thereof. The sound values of modified Latin letters can often be derived from those of the original letters. However, there are symbols that are neither. Despite its preference for letters that harmonize with the Latin alphabet, the International Phonetic Association has occasionally admitted symbols that do not have this property. Beyond the letters themselves, there are a variety of secondary symbols which aid in transcription. Apart from the fact that certain kinds of modification to the shape of a letter generally correspond to certain kinds of modification to the sound represented, there is no way to deduce the sound represented by a symbol from the shape of the symbol.

Since its creation, the IPA has undergone a number of revisions. Apart from the addition and removal of symbols, changes to the IPA have consisted largely in renaming symbols and categories, and modifying typefaces. As of 2008, there are 107 distinct letters (representing consonants and vowels) and 56 prosody marks and diacritics - glyphs or marks that may appear above or below a letter, or in some other position such as within the letter or between two letters, whose main function is to change the sound value of the letters to which they are added, although some are used to further specify these sounds and still others to indicate such qualities as length, tone, stress, and intonation.

The IPA is designed to represent only those qualities of speech that are distinctive in spoken language: phonemes, intonation, and the separation of words and syllables. The general principle of the IPA is to provide one symbol for each distinctive sound (or speech segment). This means that it does not use letter combinations to represent single sounds, or single letters to represent multiple sounds (the way that the letter <x> represents both [ks] or [gz] in English). There are no letters that have context-dependent sound values, (as the letter 'c' does in English and other European languages), and finally, the IPA does not usually have separate letters for two sounds if no known language makes a distinction between them (a property known as 'selectiveness').

Neither broad nor narrow transcription using the IPA provides an absolute description; rather, they provide relative descriptions of phonetic sounds. This is especially true with respect to the IPA vowels: there exists no hard and fast mapping between IPA symbols and formant frequency ranges, and, in fact, one set of formant frequencies may correspond to two different IPA symbols, depending on the phonology of the language in question. (I will be explaining more about how every vowel has its own distinct formant frequency in the section entitled Vowel Formants.)

The most difficult thing about learning the IPA and learning to transcribe English phonetically is breaking the habit of associating sounds with spellings. English speakers must learn the sound values for certain symbols whose IPA values are different from their most typical English spelling values. An IPA symbol always has the same sound value, regardless of who is speaking; it does not have more than one pronunciation. Therefore, the same vowel sound should be represented by the same symbol, regardless of a word's conventional spelling. This means that if two words are homonyms - they sound the same but have different meanings, as in 'heard' and 'herd' or 'cite', 'site' and 'sight' - they should have exactly the same transcription. Also, if two words rhyme, they should have the same vowel symbol (and the same symbols for any following consonants).

This is different from English spelling. In spelling, some of these sounds, especially the vowels, vary from one region of the country to another. (This is a major pitfall for the vowels. If some of the words listed in the chart below don't seem quite right to you, this may be why.)

The IPA symbols for vowels are, therefore, international standards for vowel sounds, (each having specific and unique articulatory features and auditory criteria), not necessarily for the vowels themselves. The symbol [a], therefore, does not stand for the vowel in the English word 'father', (as I might vainly attempt to tell my students). Instead, it stands for the vowel sound that is the furthest back and the lowest possible vowel in the vowel space - the vowel with the highest f1 and the closest f2 to f1 frequencies. Likewise, the symbol [o] refers to a vowel made with the tongue body in a relatively exact place, and which will therefore have the formants at certain frequencies. Any deviations from this place - any subtle change in the vocal posture that produces a slightly different sound - would also be observed on a spectrogram, through changes in the formants.

In the following sections of this article, I have endeavoured to give an example of an English word containing the vowel sounds whenever I have written about them, although, due to differences in regional accents and dialects of English, these words, when pronounced by different speakers, may produce vowel sounds that are merely similar or approximate. The sounds made by different speakers for each written vowel may differ considerably between languages or dialects within the same language. (Acoustically speaking, speech vowels are not necessarily 'pure', as they may vary considerably depending upon regional accents, producing forms of vowels that are less than uniform among all speakers. Spoken values also vary according to languages and dialects.)

Teachers should not take for granted that their own pronunciation of a specific vowel in the context of a word is also the typical pronunciation across all dialects and regional accents. As a Canadian who is teaching vocal students within the northeastern United States, I have noticed that the words that I tend to use to demonstrate the particular vowel sounds that I would like my students to use do not necessarily produce the desired results. For example, Canadian English just happens to have the vowel in 'father' very close to the cardinal position for [a], which means that when I say the word 'father', I am producing the sound that matches the sound for that particular symbol on the IPA vowel chart. In the northern U.S. pronunciation of the same word, however, the sound is more front and is not in the lowest, most far back part of the vowel space. It is not a question of whose accent is most deserving of falling into the desired category. It is a matter of accent, and accent alone.

To counter this confusion about correct 'pure' vowel sounds, a teacher may need to abandon the idea of giving examples of words containing the desired vowel sound, and instead demonstrate the ideal vowel sound in isolation (without any other context). Having no words to use in reference may be more challenging for a singer, but a few reminders and corrections during vocal exercises will eventually help the singer to memorize and correctly imitate these sounds.

Learning to truly hear the sounds in a word is another challenge for singers. This comes with practice. It becomes especially important for singers who need to be able to analyze the words of text in order to find the vowel core or the primary vowel sound of diphthongs and triphthongs.

To avoid becoming too entangled in the details of phontec transcriptions, I'd like to turn our attention to the more practical IPA symbols used for the sounds that vocalists sing the most - those pertaining to vowel sounds. Since most of my readers and students speak and sing primarily in English, I'd like to focus more specifically (and practically) on English vowel sounds.

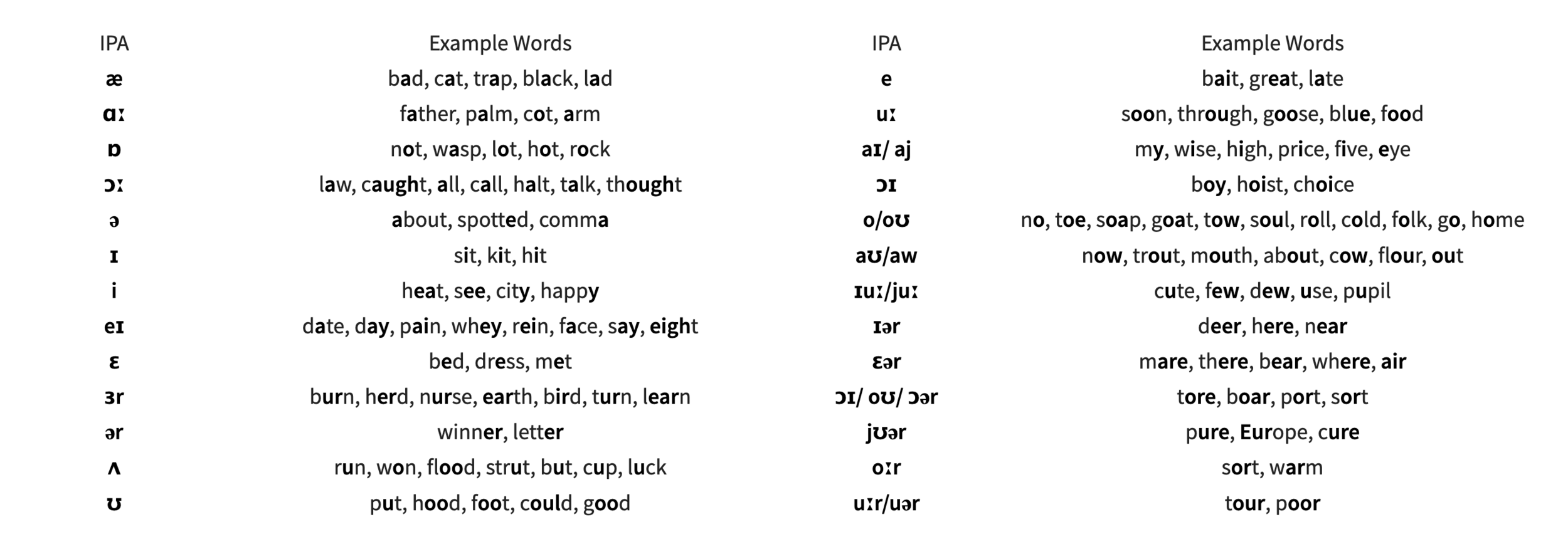

Below is a chart of the common vowel sounds found in English, their standard IPA symbols, and some words to help guide my readers to a correct pronunciation of the sound. Since the goal of IPA is that interpretation should not depend on the reader's dialect, not all of these words will be relevant to the dialects of every native speaker. Also, some sounds made in certain dialects may not be represented in this table. To clear up any confusion caused by the differences between regional accents and dialects, I have included a link to another website that enables a singer to click onto an IPA symbol for a vowel and hear an audio clip of the correct, standard, internationally accepted pronunciation of the sound.

ENGLISH VOWELS AND THEIR IPA SYMBOLS

CARDINAL VOWELS

Cardinal vowels are a set of reference vowels used by phoneticians in describing the sounds of languages. In the early 20th century, phonetician Daniel Jones developed the cardinal vowel system to describe vowels in terms of their common features: height (vertical dimension), backness (horizontal dimension) and roundedness (lip position). These three parameters are indicated in the schematic IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet) vowel diagram below. There are, however, still more possible features of vowel quality, such as the velum position (which, if lowered, contributes to nasality), type of vocal fold vibration (phonation), and tongue root position.

VOWEL HEIGHT

HIGHEST TONGUE POSITIONS OF CARDINAL FRONT VOWELS

from Wikimedia Commons

DIAGRAM OF RELATIVE HIGHEST POINTS OF TONGUE FOR CARDINAL VOWELS

from Wikimedia Commons

HIGHEST TONGUE POSITIONS OF CARDINAL BACK VOWELS

from Wikimedia Commons

Vowel height refers to the vertical position of the tongue relative to either the roof of the mouth or the aperture of the jaw. In high vowels, such as [i] and [u], the tongue is positioned high in the mouth, whereas in low vowels, such as [a], the tongue is positioned low in the mouth. The IPA prefers the terms close vowel and open vowel, respectively, which describes the jaw as being relatively closed or open. However, vowel height is an acoustic rather than articulatory quality, and is defined today not in terms of tongue height, or jaw openness, but according to the relative frequency of the first formant (f1). The higher the f1 value, the lower (more open) the vowel; height is thus inversely correlated to f1.

The International Phonetic Alphabet identifies seven different vowel heights: close vowel (high vowel), near-close vowel, close-mid vowel, mid vowel, open-mid vowel, near-open vowel, and open vowel (low vowel). The parameter of vowel height appears to be the primary feature of vowels cross-linguistically in that all languages use height contrastively. No other parameter, such as front-back or rounded-unrounded (see below), is used in all languages. Some languages have vertical vowel systems in which, at least at a phonemic level, only height is used to distinguish vowels; the vowel height is used as the sole distinguishing feature.

Although English contrasts all six heights in its vowels, these are interdependent with differences in backness, and many are parts of diphthongs - unitary vowels (contour vowels) that change quality during their pronunciation, or 'glide', with a smooth movement of the tongue from one articulation to another, as in the English words 'eye', 'boy', and 'cow'. Diphthongs often form when separate vowels are run together in rapid speech. The English language also has some triphthongs, as in certain pronunciations of the word 'flower'. These contrast with monophthongs ('pure' vowels), where the tongue is held still, as in the English word 'hat'. However, there are also unitary diphthongs, as in the English examples above, which are heard by listeners as single vowel sounds (phonemes).

VOWEL BACKNESS

The International Phonetic Alphabet identifies five different degrees of vowel backness: front vowel, near-front vowel, central vowel, near-back vowel and back vowel. Vowels are defined as either front or back not according to actual articulation (e.g., the position of the tongue), but according to the relative frequency of the second formant (f2). The higher the f2 value, the fronter the vowel. The lower the f2 value, the more back the vowel. Although English has vowels at all five degrees of backness, there is no known language that distinguishes all five without additional differences in height or rounding.

VOWEL ROUNDEDNESS

Roundedness refers to whether the lips are rounded or not. In most languages, roundedness is a reinforcing feature of mid to high back vowels, and is not distinctive. Usually the higher a back vowel is, the more intense the rounding. However, some languages treat roundedness and backness separately. Nonetheless, there is usually some phonetic correlation between rounding and backness: front rounded vowels tend to be less front than front unrounded vowels, and back unrounded vowels tend to be less back than back rounded vowels. That is, the placement of unrounded vowels to the left of rounded vowels on the Cardinal vowel chart is reflective of their typical position.

Rounding is generally realized by a complex relationship between f2 and f3 that tends to reinforce vowel backness. One effect of this is that back vowels are most commonly rounded while front vowels are most commonly unrounded. Another effect is that rounded vowels tend to plot to the right of unrounded vowels in vowel charts. That is, there is a reason for plotting vowel pairs the way they are.

Labialisation is a secondary articulatory feature of sounds in some languages. Labialised sounds involve the lips while the remainder of the oral cavity produces another sound. The term is normally used to refer to consonants. When vowels involve the lips, they are usually called rounded. The most common labialised consonants are labialized velars - a consonant with an approximant-like secondary articulation. (Labial-velar refers to a consonant made at two places of articulation, one at the lips and the other at the soft palate.)

Labialisation may also refer to a type of assimilation process. Assimilation is a common phonological process by which the phonetics of a speech segment become more like that of another segment in a word (or at a word boundary).

A related process is co-articulation, where one segment influences another to produce an allophonic variation, such as vowels acquiring the feature nasal before nasal consonants when the velum opens prematurely or 'b' becoming labialised (lips pursed in preparation for the vowel) as in "boot".

In mid to high rounded back vowels the lips are generally protruded ('pursed') outward, a phenomenon known as exolabial rounding because the insides of the lips are visible. In mid to high rounded front vowels, however, the lips are generally 'compressed', with the margins of the lips pulled in and drawn towards each other. This latter phenomenon is known as endolabial rounding. (In English, [u] is exolabial.) In many phonetic treatments, both are considered types of rounding, but some phoneticians do not believe that these are subsets of a single phenomenon of rounding, and prefer instead the three independent terms rounded (exolabial), compressed (endolabial), and spread (unrounded).

VOWEL TENSENESS

Tenseness is used to describe the opposition of tense vowels, as in 'leap' and 'suit' versus lax vowels as in 'lip', 'soot'. In the English language, 'tense and lax' are often used interchangeably with 'long and short', respectively. In most Germanic languages, (including English), lax vowels can only occur in closed syllables. Therefore, they are also known as 'checked vowels' (those vowels that usually must be followed by a consonant in a stressed syllable), whereas the tense vowels are called 'free vowels' since they can occur in any kind of syllable - they may stand in a stressed open syllable with no following consonant.

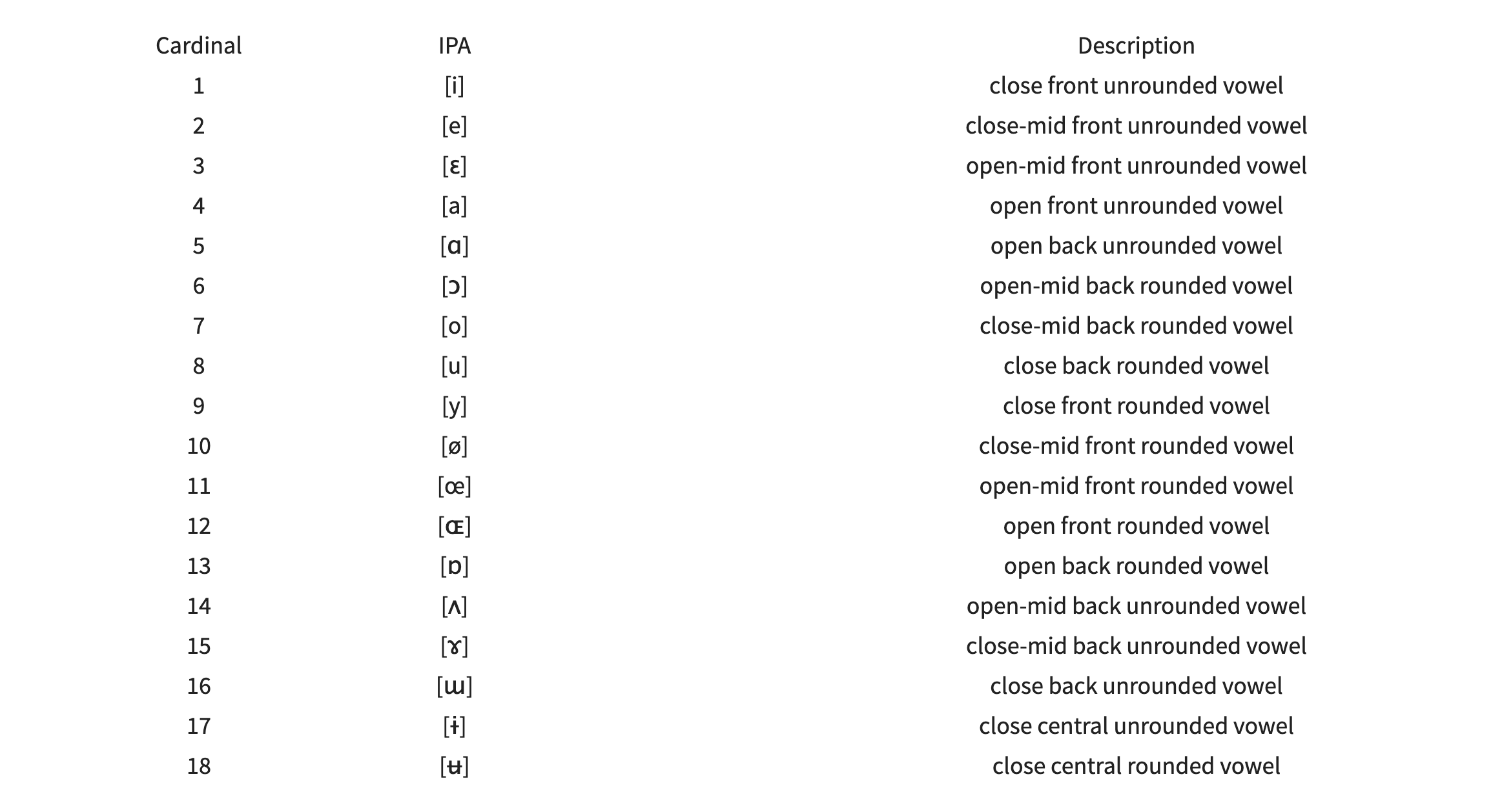

Below, I have copied a standard chart for the cardinal vowels. Again, cardinal vowels are vowels that are formed with the articulators in specific (extreme) positions. Since many new students of voice haven't had any exposure to the IPA symbols that are used for each vowel sound, I have included a link (below) to audio recordings for each sound. This link will take the reader to this same vowel chart posted on another website, where each individual symbol can then be clicked onto in order to hear the recording of the correct pronunciation. (Click onto the diagram below to be taken to the other website.)

CARDINAL VOWEL CHART

from http://www.phonetics.ucla.edu/course/chapter1/vowels.html

The vowel symbols in the IPA chart represent where in the human mouth their corresponding sounds are formed. You can imagine the chart as being superimposed on the mouth of the human that is facing to the left of this page.

Across the top of the chart, are the labels 'front', 'central', and 'back'. Front is the left most label because it corresponds with the front of a left-facing human model's mouth.

The vertical axis of the chart is mapped by vowel height. Vowels pronounced with the tongue lowered are at the bottom, and vowels pronounced with the tongue raised are at the top. For example, [ɑ], (as in 'palm'), is at the bottom because the tongue is lowered in this position. However, [i], (as in 'meet'), is at the top because the sound is made with the tongue raised close to the roof of the mouth.

Vowel backness determines the horizontal axis of the chart. Vowels with the tongue moved towards the front of the mouth, (such as [ε], the vowel in 'met'), are to the left in the chart, while those in which it is moved to the back, (such as [Λ], the vowel in 'but') are placed to the right in the chart.

In places where vowels are paired, the right represents a rounded vowel (in which the lips are rounded) while the left is its unrounded counterpart.

Three of the cardinal vowels, [i], [ɑ] and [u] have articulatory definitions that place them at the 'corners' of the vowel diagrams, with [i] and [a] having the most extreme tongue body positions, high front and low back, respectively. Other vowels are placed on the vowel chart using these three cardinal vowels as 'landmarks', with the rounded vowels always listed to the right of the corresponding unrounded vowel. (Besides being consistent, this also reflects their relative positions on formant graphs. Lip rounding will lower f2, and lower second formants are toward the right end of the standard vowel chart.)

The other vowels are 'auditorily equidistant' - meaning that there is equal spacing between the height levels that can be determined articulatorily (by making the tongue body move in four equal steps from high to low) or acoustically (by dividing the f1 dimension into four levels from lowest to highest) - between these three 'corner vowels', at four degrees of aperture or 'height': close (high tongue position), close-mid, open-mid, and open (low tongue position).

The diagrams above show the heights for the eight primary cardinal vowels. These degrees of aperture plus the front-back distinction define eight reference points on a mixture of articulatory and auditory criteria. Notice that five of the vowels are pronounced with spread lips and are consequently unrounded, while three of the back vowels are rounded vowels. Vowels like these are common in the world's languages.

The secondary cardinal vowels are obtained by using the opposite lip-rounding on each primary cardinal vowel. For example, if the feature 'rounded' for all the eight vowels is modified, the first five pronounced with rounded lips and the last three with spread lips, the secondary cardinal vowel chart is obtained. Thus, in this newly established set, all front vowels are round. (Since English does not have any front rounded vowels, this secondary cardinal vowel chart is not really relevant for the study of the vocalic system of English.)

The primary and secondary cardinal vowels are often referred to by a number, as well as their symbols.

Below is a chart depicting the vowels of the IPA that may be used as an alternative to the above cardinal vowel chart. These vowels are mapped mainly according to the position of the tongue, but also the degree of backness and the roundedness of the lips.

TABLE OF CARDINAL VOWELS

ARTICULATORY FEATURES (DEFINITIONS) OF THE 'FIVE PURE ITALIAN VOWELS'

The five pure Italian vowels - so named because their pronunciation follows that of the Italian pronunciation and because they are 'pure' monophthongs - generally refer to [e], as in 'name', [i], as in 'feet', [a], as in 'father', [o], as in 'bone', [u], as in 'boot'. Again, as stated in earlier sections of this article, the way in which I pronounce these particular vowel sounds falls in line with the IPA criteria for the sounds. The Spanish pronunciations of [ e, i, a, o, u ] are also close to their IPA values. However, not everyone may pronounce these vowel sounds in precisely the same way, so it is best to listen to these audio clips of the individual vowel sounds to know how to correctly pronounce them. These are the vowels that vocal instructors generally use, either individually or in various combinations, in training their vocal students to balance their singing tone. Learning to pronounce these sounds correctly allows for more consistency in vocal training, as teachers and students will be on the same 'acoustic' page, and because their formant frequencies are easily tracked.

Each of these vowels has its own unique articulation, giving it its own unique characteristics and qualities. The articulatory features that distinguish different vowel sounds are said to determine the vowel's quality, (by establishing their individual formant frequencies).

The features of the vowel [e] - a close-mid front unrounded vowel - include a vowel height that is close-mid, which means that the tongue is positioned halfway between a close vowel and a mid vowel. Its vowel backness is front, which means the tongue is positioned as far forward as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant. Its vowel roundedness is unrounded, which means that the lips are not rounded.

In the close front unrounded vowel [i], its vowel height is close, which means that the tongue is positioned as close as possible to the roof of the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant. Its vowel backness is front, which means that the tongue is positioned as far forward as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant. Its vowel roundedness is unrounded, which means that the lips are spread.

In an open back unrounded vowel, such as [a], the vowel height is open, which means that the tongue is positioned as far as possible from the roof of the mouth. The vowel backness is back, which means that the tongue is positioned as far back as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant. The vowel roundedness is unrounded, which means that the lips are not rounded.

[o] is a close-mid back rounded vowel, which means that it has a vowel height that is close-mid, which means that the tongue is positioned halfway between close vowel and a mid vowel. Its vowel backness is back, which means that the tongue is positioned as far back as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant. Its roundedness is endolabial, which means that the lips are rounded and protrude, with the inner surfaces exposed.

The vowel height of the close back rounded vowel [u] is close, which means that the tongue is positioned as close as possible to the roof of the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant. Its vowel backness is back, which means that the tongue is positioned as far back as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant. Its roundedness is endolabial, which means that the lips are rounded and protrude, with the inner surfaces exposed. This sound can be approximated by adopting the posture to whistle a very low note, or blow out a candle.

VOWEL FORMANTS

Each phoneme is distinguished by its own unique pattern in the spectrogram. Spectrograms display the acoustic energy - formants, which appear as dark bands - at each frequency, and how this changes with time. For voiced phonemes, the signature involves large concentrations of energy (formants). During voicing, which is a relatively long phase, the spectral or frequency characteristics of a formant evolves as phonemes unfold and succeed one another. Formants that are relatively unchanging over time are found in the monophthong vowels and the nasals; formants which are more variable over time are found in the diphthong vowels and the approximants, but in all cases the rate of change is relatively slow.

Within each formant, and typically across all active formants, there is a characteristic waxing and waning of energy in all frequencies. This cyclic pattern is caused by the repetitive opening and closing of the vocal folds, which occurs at an average of 125 times per second in the average adult male, and approximately twice as fast (250 Hz) in the adult female, giving rise to the sensation of pitch.

The vocal tract acts as a resonant cavity, and the positions of the jaw, lips, and tongue - as in the articulation of specific vowel sounds - affect the parameters of the resonant cavity, resulting in different formant values.

The information that humans require to distinguish between vowels can be represented purely quantitatively by the frequency content of the vowel sounds; that is, the different vowel qualities are realized in acoustic analyses of vowels by the relative values of the formants - the acoustic resonances of the vocal tract. Each vowel has its own distribution of acoustic energy that distinguishes it from all other vowels. Vowels will almost always have four or more distinguishable formants. However, the first two formants are the most important in determining vowel quality and in differentiating it from other vowels.

Each vowel, therefore, has its own 'fingerprint', which is defined or characterized by its unique frequencies at the first and second formants. These formants are usually referred to as the 'vowel formants'. They are not adjustable for each given vowel or variant of each vowel. For example, the formant frequencies for the [i] vowel for any given voice are more or less constant and remain within very specific limits in the frequency range. For this reason, these vowel formants may also be called 'fixed formants'. If these vowel formants are not produced by the vocal tract, the particular vowel can't exist. Conversely, whenever the formants for a particular vowel are present, that vowel is heard.

The chart below shows the individual values (frequencies) for the first and second formants for each of the five pure Italian vowels. While it isn't necessary for a student of voice to memorize these specific frequency ranges (formant values), knowing which vowels have higher or lower formants - both the first and the second - will aid in the process of formant tuning.

VOWEL FORMANT CENTRES

These formants can be experienced by gently thumping the side of the larynx with a finger while mouthing the five pure Italian vowels [e, i, a, o, u]. The [i] and [u] vowels have the lowest resonance of the vocal tract, whereas the [a] vowel has the highest resonance, while the [e] lies somewhere in between. These are the first formant, (abbreviated as f1), resonances for these vowels for your particular voice. If you modify these vowels, you will hear other f1 resonances for the modified vowel.

Each vowel has its own laryngeal configuration, and there is a corresponding vocal tract configuration that permits a specific vowel to take on its distinctive form. It is impossible to get a one to one relation between given articulatory features and the formants' values, as a lot of variables play a role in this phenomenon. Also by removing the speaker specific parameters, every formant is determined by the joint effect of different articulatory characteristics, (which includes vowel height, backness and roundedness).

However, a positive relation can be assessed, respectively, between the degree of closing (vs. opening) of the oral cavity and the f1 values, and between the degree of back displacement (vs. front displacement) of the tongue and the f2 values. For example, [i] has a relatively low f1 value, because the oral cavity is rather closed, and a high f2 value, because the tongue is displaced to the front, while for [a], it is the other way round. In particular, in back vowels such as [a], the f1 and f2 values are closer to each other, while in front vowels they are more distant. Vowels traditionally known as 'front' have f1 and f2 a good distance apart. Vowels traditionally known as 'back' have f1 and f2 so close that they touch.

The first formant increases in frequency as the vowels go from close to open. As can be seen in the chart above, the first formant (f1) has a higher frequency for an open vowel, such as [a], and a lower frequency for a close vowel, such as [i] or [u].

The second formant increases in frequency as the vowels go from back to front. The second formant (f2) has a higher frequency for a front vowel, such as [i], and a lower frequency for a back vowel, such as [u].

The third formant (f3) is involved in the differentiation between rounded and unrounded vowels (e.g., the difference between [i] and [y]).

A vowel is called compact when f1 and f2 are close together, such as [a], and diffuse when they are far apart.

There are certain 'rules' that help acousticians predict the formant structure of vowels. First, the area of the major constriction determines the location of f1; as the area decreases, f1 also decreases. Second, the distance from the glottis to the major constriction determines the location of f2; as distances increases, f2 also increases. Third, for a given area and distance from the glottis of the major constriction in a vowel, lip rounding causes f1 and f2, especially f2, to fall. Thus, the back vowel [u] has a lower f2 than the second rule alone would predict because the lips are rounded when pronouncing this vowel.

The front, closed vowel [i], for instance, has acoustic strength in the upper part of the spectrum near the region of the Singer's Formant, whereas the more neutral, open vowel [a] has its acoustic strength at the bottom half of the spectrum. The back vowels [o] and [u] are defined at increasingly low acoustic levels.

The first formant corresponds to the vowel openness (vowel height). Open vowels have high f1 frequencies while close vowels have low f1 frequencies. [i] and [u] have similar low first formants, whereas [ɑ] has a higher formant. [ɑ] is a low vowel, so its f1 value is higher than that of [i] and [u], which are high vowels. [i] is a front vowel, so its f2 is substantially higher than that of [u] and [ɑ], which are low vowels.

The second formant, f2, corresponds to vowel frontness. Back vowels have low f2 frequencies while front vowels have high f2 frequencies. The front vowel [i] has a much higher f2 frequency than the other two vowels. However, in open vowels the high f1 frequency forces a rise in the f2 frequency, as well, so an alternative measure of frontness is the difference between the first and second formants. For this reason, some people prefer to plot as f1 versus f2 - f1. (This dimension is usually called 'backness' rather than 'frontness', but the term 'backness' can be counterintuitive when discussing formants.)

During voicing, which is a relatively long phase, the spectral or frequency characteristics of a formant evolves as phonemes unfold and succeed one another. Formants that are relatively unchanging over time are found in the monophthong vowels and the nasals; formants which are more variable over time are found in the diphthong vowels and the approximants, but in all cases the rate of change is relatively slow.

PRACTICAL GUIDELINES FOR SINGING VOWELS

Most vocal training is done using the 'five pure Italian vowels'. It is assumed by teachers that using these 'landmark' vowels in training will enable their students to sing any vowel, because other vowels are merely modified forms or variations of them, requiring very slight adjustments of the vocal tract in order to articulate them. Keeping vocal training to just five vowels also makes sense from a practical standpoint, as time during lessons is limited, and there is simply no way to train intensely on all vowels.

It is estimated that we actually have between twelve and fifteen vowel sounds commonly used in the English language. These additional vowel sounds can be found in the IPA Vowels and Symbols chart, along with some words that include these sounds.

Vowels are properly formed at the front of the mouth. The back of the tongue must remain stable - neither raised nor depressed into the larynx. The middle of the tongue forms the individual vowels, and the tip of the tongue should remain in its resting place behind the lower front teeth, except in the formation of certain consonants.

As explained in Singing With An 'Open Throat': Vocal Tract Shaping, it is important for a singer to initiate phonation (sound) with an open pharynx, high soft palate and relaxed, low larynx. Many students of voice, however, begin singing their vowels with closed vocal tracts, with the back of the tongue pressed up against a lowered soft palate, and the vocal folds too tightly closed. In speech, this kind of pressed phonation is very common, although we don't notice it as much because we don't sustain our vowels for as long as we do during singing, and because the consonants that usually begin syllables buffer this effect.

Say the vowel [a], for example, and pay close attention to how the back of the tongue and soft palate touch, closing off the acoustical space, before the vowel is spoken. When phonation begins, these articulators must separate from each other. The vocal folds themselves are also firmly closed, which then requires more air pressure to blow them apart and set them vibrating. You will notice that the same thing likely happens with all spoken vowels (when spoken either in isolation or at the beginning of a word).

During many vocal exercises, the vowel is not preceded by a consonant, so this tendency toward pressed phonation becomes more pronounced during training than during the singing of text. Many students- voices sound 'pressed' or squeezed at the onset of the vowel because they tend to maintain the same habits that they have during speech. For many singers, this overly firm onset gives a sense of (or provides the illusion of) clearer definition to the vowels that they are singing, but it should not be mistaken for correct, efficient and healthy onsets of sound. In fact, pressed phonation can lead to vocal injury, and it also strips away some of the pleasantness of the tone due to its negative acoustical effects.

It takes some retraining for singers to learn to open up the acoustical space first, and then begin phonating (producing sound) without this kind of 'closed throatedness'. I often tell my students to picture the acoustical 'tube' (vocal tract) being open right from the start, before sound is made - this correctly takes place when the singer is preparing to sing (i.e., at the time of inhalation) - and then allow the air and sound to pass through the already open spaces of the throat and mouth.

To learn to establish the openness in the throat before singing the vowel, a singer can use the neutral vowel 'UH', as in the word 'good', in the larynx before bringing focus into the tone. For example, start with the 'uh' in the larynx and then bring the tongue forward as in the [i] vowel. The open pharynx is established first, so that the brilliance of the tone can follow while keeping the open feeling in the throat.

Because of this tendency to begin phonation of vowels with a closed throat, it is essential for students to spend a great deal of time vocalizing solely on vowels. If a teacher has a student always insert consonants before all vowels during exercises, it is quite possible that this pressed phonation may slip under the radar. Once a singer learns to consistently maintain an open vocal posture during the singing of vowels, and especially at the start of them, consonants can then be added to the exercises. The teacher and student can then be reassured that the mode of phonation is healthy and that tonal balance will be achievable.

Vowels are the most important element of singing because they produce the greatest acoustical energy. All sustained notes, therefore, should be vocalized on the vowel sounds, not on consonants, which have higher levels of impedance, and therefore do not resonate as effectively. Singers must be careful not to sing the consonants at the end of syllables prematurely, which will add a constriction to the resonating space and thus limit resonance and volume. The vowel sounds must be held for a long as possible, with the consonants being added only at the last possible second.

While training on vowels is very important to good vocal training, including the singing of text (words, sentences, songs, etc.) to training methods enables a singer to practice singing different variations of vowels in different combinations with consonants. The singing of text represents an important 'application' aspect of vocal training. Balanced training will have the singer vocalizing on all of the applicable vowel sounds heard in the English language.

Having my students vocalize mainly on the five pure Italian vowels has revealed some unique tendencies and problems associated with the production of each of these vowels.

The most common tendency for vocalists (in most English dialects) when singing the vowel sound [e], as in 'late', is to sing the vowel sound as a diphthong. It usually takes a little practice to find the more pure version of this vowel sound, allowing the initial vowel sound to be held as the vowel core.

A lot of students of voice struggle with the vowel sound [i], as in 'meet', because it is a lateral or fronted vowel, making it very 'closed'. Many students have difficulties maintaining openness in the vocal tract, and this vowel will often sound tight or 'squeezed', especially in the upper middle and the head registers. In the middle register, many singers tend to flatten the tongue in order to darken this vowel, which creates a muffled, distorted sound to the vowel. In head voice, many students have difficulties with thinness or shrillness (too much brightness) in the tone when singing such close vowels. Other singers, however, actually find this vowel easier to sing than more open vowels because they find it easier to keep breathiness at bay, and because its relatively low f1 value and high f2 value often create a louder, more resonant sound inside the singer's internal hearing.

The vowel sound [a], as in 'father', can be particularly problematic for some students, as the sound has a tendency to 'fall back' into the throat. In most phonetic systems, the vowel [a] is considered to be the primary, or first, of the back vowel series. (In some others, it is the first of the neutral vowel series). During normal speech and in unskillful singing, back-vowel production typically brings a loss of upper partials (upper harmonic overtones). This loss of upper partials becomes particularly apparent when this vowel follows a front vowel, such as [i] or [e] because a downward acoustic curve occurs in which the perception of the pitch centre of the vowel lowers. A spectrum will display a loss of upper harmonic partials. The vowel-defining second formant, which together with the first formant largely identifies the vowel, demonstrates a downward stepwise progression. The vowel, then, sounds too dark. When the singer learns to retain the third, fourth and fifth formants, regardless of the progressing from lateral to rounded vowels, no vowel will 'fall back'.

Also, being an open vowel, many singers tend toward breathy phonation while singing the [a] sound. Many students find this vowel to be more comfortable than more close vowels to sing, and may relax their breath support and vocal fold approximation as a result.

The vowel sound [o], as in 'note', has two different 'phases' in its production. In speech, the mouth is more rounded and more open at the beginning of the vowel than it is at the end of the vowel. At the end of the vowel, the lips become pursed, which creates an [u] sound, making the vowel a sort of diphthong. A singer must be very careful not to allow the lips to come forward at any point during the singing of the vowel [o]. I always encourage my students to maintain the core of the vowel; that is, to sing only the beginning of the vowel, with the lips nicely rounded and the mouth in a circle. Otherwise, the vowel begins to sound like another vowel, [u]. In contemporary genres, it is more acceptable to allow the lips to move forward to complete the vowel as it would be completed during speech to allow for better diction and word recognition, but only at the very last possible second.

A common difficulty with the vowel sound [u], as in 'shoe', is that the tone becomes overly dark and 'hooty' sounding. Again, as a singer proceeds from front to back vowels, the spectra undergo significant changes, which brings about a reduction or loss of upper partials. [u] is the final member of the back-vowel series. In speech, it tends to sound darker or duller than do front vowels, and lower in pitch than even neighbouring back vowels. (I'll explain in the section on vowel modification that all vowels have their own pitch.)

Any tendency to pucker the mouth into a small, rounded opening for the production of [u] removes overtone activity. The upper lip should not be pulled downward, covering the upper teeth, because the zygomatic muscles would then be lowered toward the grimacing posture. This gesture alters both internal and external shapes of the resonators.

Also, avoid the tendency to allow the lower jaw to slide forward during the production of the [u] vowel sound.

NASAL VOWELS AND NASALIZATION

Nasal vowels are vowels that are produced with a lowering of the velum, so that air escapes through the nose as well as the mouth. (They stand in contrast to oral vowels, which are ordinary vowels without nasalization, in which all air escapes through the mouth.) Nasalization refers to a situation whereby some of the air escapes through the nose during speech or singing.

In English, there is no phonemic distinction between nasal vowels and oral vowels, and all vowels are considered phonemically oral. However, vowels preceding nasal consonants tend to be nasalized; that is, vowels that are adjacent to nasal consonants are produced partially or fully with a lowered velum in a natural process of assimilation - see co-articulation, above - and are therefore technically nasal, though few speakers would notice. North American speech itself is characterized by a high degree of nasality, with sound partially emitted through the nose on nonnasals (low velar posture producing an open velopharyngeal port). The vowels in words such as 'come', 'home', 'man', 'found', and 'sang' tend to adopt the nasality of the succeeding or preceding nasal consonant.

Many students of voice tend to nasalize vowels that are adjacent to nasal consonants when they sing lines of text, although few are aware of it, likely because hypernasality is becoming increasingingly prevalent in popular music, so much so that they have become accustomed to hearing nasally tones from most of their vocal role models.

In the third paragraph of this article, I stated that a singer's goal should be to learn to sing vowels without allowing the consonants to get in the way. Also, nasality, apart from that which naturally occurs during intended, intermittent nasal phonemes, is generally considered to be an undesirable tone in singing, and is a less acceptable and technically incorrect vocal element in most genres of music. Therefore, this tendency to nasalize vowels should be avoided during singing. (It should be recalled that opening up the nasal cavity during singing produces antiresonances, which rob the voice of its overtones and decrease natural volume.)

Even in languages that incorporate nasal vowels, such as French and Portuguese, the nasal quality is generally added only to the end of the phoneme or sung vowel so that resonance in the vocal tract can be maximized throughout the sustained note, and so that all active formants of the oral vowel can be present and strengthened. The introduction of nasality into the sustained nasal syllable is delayed or deferred until just before its termination, except where the note is very quick, which requires near immediate nasalization of the syllable. Even when nasality is necessary in order for correct pronunciation of the language, a very small amount of nasality will suffice.

With my students, we work through lines of text and analyze the quality of each vowel being sung. We break down the individual phonemes to ensure that the core of the vowel - that is, the part of the vowel that is being sustained - is pure, rather than nasalized. Incorporating repertoire into technical training becomes particularly useful for the student, because successfully vocalizing on vowels alone during vocal exercises does not necessarily guarantee that a student will also successfully maintain the purity of the vowels during the singing of songs when consonants are added. Students tend to have different habits when singing complete words and lines of text than they do while singing single vowels. Natural linguistic patterns require the juxtaposition of all possible spoken phonetic combinations, as occurs in poetic texts set to music.

Even in technical training exercises, it is often beneficial for the singer to combine nasal consonants with vowels in order to encourage rapid and immediate velar shifting from open to closed nasal port or closed to open nasal port, as happens frequently during speech and during the singing of text. If unwanted nasality from an adjacent nasal consonant becomes added to the vowel, a singer can try occluding the nostrils between the thumb and the first finger (pinching the nose) whenever a vowel or nonnasal consonant is being sung. (The nasal cavity must remain open for the nasal consonants, though.) For example, if singing 'maw', the singer would pinch the nose at the conclusion of the 'm' and the beginning of the oral vowel. Variances in timbre and sensation between the nasal and nonnasal sounds can readily be identified. The singer should also feel an immediate lifting of the velum and closure of the nasal port. This sound and sensation should be memorized so that the singer can learn to consistently avoid nasalizing vowels.

For more information on how to eliminate undesirable nasality from your tone, please read the section on nasally tone in Good Tone Production For Singing.

R-COLOURED VOWELS

R-coloured vowels, also known as rhotic or rhotacized vowels, are heard in words such as the Midwestern American English pronunciation of 'fur' and 'air' and before a consonant as in 'hard' and 'beard'. IPA hangs a little 'r-hook' diacritic off of the symbol for an r-colored vowel, as can be seen in the English Vowels and Their IPA Symbols Chart. The English vowel may be analyzed phonemically as an underlying /ǝr/ rather than a syllabic consonant.

R-coloured vowels are also known as vocalic 'r's. (In English, the vocalic r occurs as an r-coloured vowel.) In the vocalic r, the rhotic segment (e.g., the [r] or [ɹ]) occurs as the syllable nucleus - the nucleus, (sometimes called its peak), is the central part of the syllable, most commonly a vowel - in words like 'butter' and 'church'.

R-coloured vowels occur in a number of rhotic accents of English, like General American. These vowels are absent in 'r-drop' or non-rhotic dialects, such as those typical of the North American South and New England region, and Received Pronunciation in Great Britain. In these latter dialects, the preceding vowel is usually lengthened and often glides toward the central schwa sound - the schwa is a reduced vowel (acoustically changed or weakened) sound that usually occurs on unaccented or unstressed syllables (lightly pronounced) in words containing more than one syllable. Schwa is a very short neutral vowel sound, and like all vowels, its precise quality varies depending on the adjacent consonants. It is sometimes signified by the pronunciation 'uh' or symbolized by an upside-down, rotated 'e'.)

During at least part of the articulation of the vowel, an r-coloured vowel may have either the tip or blade of the tongue turned up - (this is known as a retroflex articulation, in which the tongue articulates with the roof of the oral cavity behind the alveolar ridge, and may even be curled back to touch the hard palate; that is, they are articulated in the postalveolar to palatal region of the mouth) - or with the tip of the tongue down and the back of the tongue bunched. (American English typically curls the tip of the tongue back towards the palate.) Both articulations of r-coloured vowels lower the frequency of the third formant.

R-coloured vowels are a particular challenge for singers because they can hinder the production of, as well as distort, pure vowels. Folk and Irish singers, performers of country music, as well as singers with certain regional accents, tend to have very pronounced r-coloured vowels while singing.

Many vocalists who would normally speak English with r-colored vowels will replace them with their non-rhotic equivalents when singing in English. Since the first and second formants of words like 'bird' are often very similar to those of the word 'hood', the singer can create a nicer tone by removing the 'r-colouring' from the vowel and singing the 'UH' sound, as in the latter word. The key to singing r-coloured vowels while avoiding the characteristic acoustical distortion and lowering of the third formant is to examine the vowel preceding the 'r', then attempt to sing this open vowel, adding the 'r' sound only at the end of the sung phoneme.

For some singers, the concept of softening their 'r's to make them less pronounced works at creating a nicer sound while still maintaining diction.

MONOPHTHONGS AND DIPHTHONGS

The English language is made up of different types of vowels, including compound vowel structures that the student of voice needs to learn to sing as purely as possible.

A vowel sound whose quality doesn't change over the duration of the vowel is called a monophthong. Monophthongs are sometimes called 'pure' or 'stable' vowels. The words 'hat' and 'not' are examples of monophthongs.

A vowel sound that glides from one quality to another is called a diphthong. In most dialects, 'boy' is a diphthong.

The vowel sound in the word 'my' is a diphthong. Separating the sound into its composite vowels yields two distinct vowel sounds: 'ah' and 'eeh'. When singing diphthongs, the first vowel sound is sustained primarily, and the second vowel sound is added at the very last second in order to make the word distinguishable. This technique helps to stabilize the vowel by allowing full resonance to be achieved on a single, pure vowel, since monophthong vowels have better spectral continuity.

VOWEL MODIFICATION ('COPERTURA')

Vowel modification is an intentional, slight adjustment made to the sound (acoustics) of a vowel, by altering the basic way in which a vowel is articulated, with the goal of attaining more comfortable and pleasing tone production, especially in the higher part of the singer's range. It is a conscious equalizing of the ascending scale. Some singers make these vowel modifications naturally and correctly, without even being aware them. Many singers, however, resist the natural tendencies of the voice, struggling to sing vowels exactly as they sound in speech all the way to the top of the voice's range because they believe that they are supposed to. It then becomes necessary for them to learn the subtleties of singing vowels in the upper extension.

In a futile attempt to promote better blending of voices and clarity of diction within their groups, some ill-informed choir directors and teachers will instruct their choir members or students to use only speech vowels - vowels that are pronounced in the exact same way that they would be during speech, regardless of pitch. However, singing the exact vowels that are written by the composer is illogical and unnatural to the vocal instrument, as I will explain further in the following sections. Insistence upon singing the vowel written on the page will inhibit or prevent the natural ability of the singer to find the modification that serves the needs of the music and the voice.

By avoiding vowel modification as part of their technical training, voice teachers and singers ignore a means of producing a more resonant, carrying tone, and a more healthy, efficient way of achieving it, not to mention more control over dynamics and more ease in upper range singing.

A failure to correctly modify vowels throughout the changing scale will inevitably result in problems such as the inability to stay in tune in the area of the register breaks (passaggi) - faults in singers' hearing are seldom the root cause for unintentional pitch deviations - other assorted intonation problems, adverse effects of consonant production on formant tuning and tone quality, resonance problems across the range (imbalance), an inability to sing at a soft dynamic level without losing the fundamental of the pitch, breathiness in the middle register, an inability to 'cover' (protect) the tone, an inability to access the head register, poor breath management and unclear diction and blending difficulties. All of these technical problems create a faltering and inept performance, since singers who are experiencing register problems find it difficult, if not impossible, to handle the musical and vocal problems that occur at the passaggi, and since imbalance of tone and an inability to sing at different dynamic levels limits the singer.

To avoid these artistic limitations, the proper muscular activities need to become almost reflexive. During singing, good interactions between the vocal folds, which produce the initial sound ('buzz') of the voice, and the vocal tract, which resonates that sound, are essential. These two parts of the vocal instrument should augment, rather than fight, each other.

Singers should sing vowels that free up the voice. When vowels are correctly modified, the singer experiences more comfort, the tone is more beautiful, and the air supply lasts longer. With the aid of vowel modification, singers will have fewer intonation problems, better resonance across their ranges, more carrying power, easier production of forte (loud) and piano (soft), clearer diction, and a much better blend. Furthermore, when the vocal tone is correctly formed by acoustical phonetics, the singer avoids many muscular problems, including hyperfunction and hypofunction, both of which may result in 'stiffness' of parts of the vocal tract, and can translate into hoarseness, register problems, unacceptable deviations from the pitch, limitations of range, color, and dynamics, poor vibrato, as well as other malfunctions and/or dysfunctions.

In my view, vowel modification is linked to two major aspects of singing: acoustics (including optimal resonance, balance of tone and smooth registration) and protection of the vocal instrument through correct and healthy laryngeal adjustments. In singing, one must learn to coordinate the acoustic and physiologic events of vowel definition while at the same time taking into account the relationships (and adaptations) of speaking to the singing voice. Only when these factors are coordinated can balanced resonance, with the upper partials that give the professional voice its characteristic chiaroscuro (balanced) timbre, be fully realized. Below, I have attempted to discuss the concept of vowel modification from these two perspectives. (It is impossible to completely separate these two aspects of vowel modification, since one affects the other.)

ACOUSTICS

The vocal instrument, like all other instruments, is responsive to the laws of acoustics. When the vocal tone is correctly formed by acoustical phonetics, the singer creates a more pleasing, carrying tone, and avoids many muscular problems.

Vowel modification is an extended method of bringing the frequencies of the vocal folds and the vocal tract into accord with the various pitches and vowels. (This is known as the process of 'formant tuning'.) Although it is possible for a vocalist to sing any vowel on any note within his or her range, some vowel forms will have better acoustical interactions with the vocal folds, aiding and amplifying their air pressures more effectively, while other vowel forms will have diminishing acoustical interactions with the vocal folds.

Modifications, which are achieved by making small adjustments to the size and shape of the vocal tract, persuade the resonator (vocal tract) to work efficiently, which creates optimal resonance and balance of tone. When the resonator adjusts so as to amplify the sung pitch, the vowels are, in that instant, automatically modified. For example, when female singers lower their jaws while singing [i] in the head register, they are modifying the vowel, as [i] sung with a slightly larger mouth opening will become a soft (or short) 'i', as in 'bit' and 'fish' or [ɛ], as in 'bed', if the jaw is lowered yet a little further. This kind of modification has positive effects on tone as well as vocal health, as it brings sung pitch and the resonance of vowels into their best relationship.

Some misguided teachers and choir directors instruct their students and choir members to sing all vowels using the same mouth shape throughout the range. However, it is impossible to maintain one vowel position at all pitches. If vowel positions are kept in a fixed state rather than modified, the voice will run into and out of resonance points, resulting in a sound that is out of tune, harsh, unfocused, and unsteady in vibrato rate.

Some choir directors and vocal coaches may ask their choir members and students to use what they believe to be 'pure vowels' - by 'pure vowels', they generally mean vowels that sound exactly as they do during speech - throughout a song in order to encourage clarity of diction. Although singing the vowel precisely as it would be pronounced during speech and exactly as the composer wrote it would be logical, it is not natural to the vocal instrument. Our ability to produce speech vowels (absolute language values) throughout the vocal range is a misconception because the vocal instrument simply does not work that way.

In fact, the more that the sounds of speech vowels are approximated during singing, the more inharmonic the voice will become. For example, some students vainly attempt to maintain the same spread mouth position of [i] that is used during speech above the upper passaggio, refusing to allow for the rounding that is necessary in order to facilitate a smooth transition into the head register. The voice inevitably begins to sound increasingly thinner, 'squeaky' and more strained, or it cuts out completely. The voice simply can't work the same way in the upper extension that it does in the lower range.

The most notable example of a singer's inability to maintain vowels as they are spoken is when a female singer is singing notes in her upper range. Experienced composers understand this and write accordingly. High notes and very dynamically intense notes are usually musical events, not text events, and words are typically abandoned in favour of vocalises (wordless vocal 'gymnastics') during climactic moments in order to avoid having an uncontrolled and unattractive tone. On high pitches, the emphasis is on vocal skill - the beauty and impressive sound of the voice - rather than on diction skills.

Adherance to speech vowels produces tonal interferance because of the incompatibility of the vowels and pitches, which, in turn, destroys rather than promotes clear diction. Not only does avoiding natural acoustical adjustments create tonal imbalance, but it also risks numerous technical and health problems. Singers who utilize many non-harmonic sounds (speech vowels) that conflict with the written pitches do not sing as long because this practice is physically unhealthy. When asked to sing speech vowels in the higher parts of their ranges, singers will experience vocal unease and difficulty - including discomfort, a tone that is lacking in beauty, a serious diminution of the air supply, a reduction in carrying power, uncontrollable pitch inexactness (either flat or sharp, but most oftentimes flat) that are not controllable even when a singer is acutely aware of them, and deteriorating vocal health over time. The practice of singing only so-called 'pure' vowels is, therefore, illogical and unhealthy. (I will discuss this practice from a health perspective in the following section on vocal protection.)

Acoustically speaking, these speech vowels are not necessarily 'pure', anyway, as they may differ somewhat from speaker to speaker. In addition, speech vowels vary considerably depending upon regional accents, (as I've already discussed in the first few sections of this article). The results are, therefore, less than uniform and less than 'pure'. This fact means that neither diction nor resonance will be aided by singing speech vowels. Whereas spoken vowel values vary according to languages and dialects, in singing, vowels must always be compatible with vowel pitch and the harmonic of the sung pitch. (This is one of the reasons why people can sing in a foreign language without an accent but cannot speak it without an accent.)

Regarding intelligibility of diction as it relates to vowel modification, research has shown that, once a voice reaches the pitches of its high passaggio, the human ear can no longer perceive the difference between that same voice singing one front vowel or another, one back vowel or another. Furthermore there are acoustic regions where more than one vowel intersect. This means that one vowel adjustment will sound like two or even three different vowels depending on context (surrounding consonants, etc.). (I have written more about the female upper register and why vowels can't be easily distinguished at higher pitches in the article entitled Singing With An Open Throat: Vocal Tract Shaping, also posted on this website.)

Intelligibility, therefore, does not mean that someone is singing the spoken form of a vowel. Since the listener cannot perceive the difference between certain vowels that have similar qualities at high pitches, it makes no sense to attempt to sing a vowel that is incompatible with the sung pitch and that is more difficult (and possibly uncomfortable) to execute. Besides, at these high pitches, intelligible diction is still possible because it is the consonants (and their positions in relation to the vowels) that play a larger role in distinguishing words.

Even though a singer or choir director may resist natural vowel modification, this avoidance doesn't change the fact that vowels cannot be sung as they are spoken. This is true throughout the range because every note has a different resonance necessity, and therefore a different formant balance due to its unique vocal tract configuration.

It's important to understand that vowel modification doesn't just happen in the high range of a singer's voice (i.e., upper middle and head registers). A singer whose vocal resonance is even and consistently good from note to note - high or low, soft or loud - is changing the vowels semitone by semitone, and the vocal tract is constantly changing form. Good singers, whether consiously or not, depend on finding an easy adjustment, or modification, for the pitch. These modifications may not be easily perceived by the listener, and the singer may not even take note of them, but they do happen throughout the range, even within speech inflection range. In fact, vowels are naturally and effortlessly modified during speaking tasks, as inflection rises or lowers and as volume changes, although we are not aware of these subtle adjustments because they occur so commonly and instinctively.

The fact of the matter is that bad sound is far more noticeable than slight modifications of language values. It therefore makes sense to allow for natural resonance adjustments created by vowel modification.

Those experts who really understand the acoustics of the voice - acousticians - consider a pure vowel to be one that delivers ease, beauty, and resonance on that particular pitch. True vowel purity, then, is the optimum acoustical response for a given vowel. When the most resonant vowel on a particular sung note is found, it is invariably different from the one used in speech patterns.

Adopting acoustical (modified) vowels instead of speech vowels will benefit the singer in the areas of the tonal balance and vocal health.

Both vowels and sung tone have pitch. The pitch of the vowel being sung must be harmonic with the sung pitch, or there will be a weakening of the vocal fold vibrations, which may be accompanied by an 'untuning' of the tone. When the vowel is incompatible with the sung pitch, the singer may experience anything from slight discomfort all the way to actual pain, the tone will be anywhere from slightly less than beautiful all the way to actually ugly and unpleasant, and the air supply will be diminished radically because it takes more air to sustain an inappropriate vowel. Inflexible language treatment - that is, insisting that all vowels be sung exactly as they would be spoken - tends to impair the musicality, expressiveness, and survival of voices. (This is why an unknowledgeable teacher who insists on treating diction inflexibly can do a great deal of harm to his or students by ignoring the laws of vibration and resonance.)

With acoustical vowels, the harmonic values of the pitch coincide with the pitch of the vowel itself. They therefore produce optimal amplification of resonance, giving the voice more size and carrying power, (which is especially important in unamplified singing), as well as a physiological feeling of well-being (versus a feeling of tension, discomfort or pain), vibrancy ('ring' and vibrato) and pitch centeredness - almost always, the use of acoustical vowels in singing produces tones that are in the centre of the pitch. Singing with the best relationship of the larynx (vibrator) and the vocal tract (resonator) is healthier (e.g., singers who use harmonic sounds, or modified vowels, sing for a long time because they are more therapeutic for the throat), more pleasing to the ears, and aids in breath coordination (lengthens the air supply).

The core of the vowel, which itself is achieved by specific articulatory definitions (e.g., the size of the jaw opening, the shape of the lips, and the position of the tongue), is also the core of the pitch when that vowel is sung rather than spoken. Each vowel has a quality that is unique to that particular vowel, a quality that names the vowel or makes it what it is. (Earlier in this article, in the Vowel Formants section, this quality of the vowel was referred to as its individual 'fingerprint'.) The vowel core, then, is the identifying quality. It is also an acoustical phenomenon. For example, when the vowel is identified precisely, the resonance chambers of the vocal instrument are immediately re-shaped so that optimum amplification of the basic sound is achieved. The singer then has greater volume and potential for dynamic variation, as well as improved intonation and greater ease of production.

Also, the use of acoustical vowels aids, rather than detracts from, diction. Speech recognition, which all teachers and singers desire, is dependent upon the changing shapes of the filtering resonator tracts above the larynx. A knowledgeable teacher understands this delicate and ideal interaction, and can help his or her students accomplish a great deal by obeying the laws of harmonic pronunciation.

Vowel modification must be mastered in order to facilitate smooth transitions throughout the range - from low to high and from soft to loud. As a basic rule, the louder or higher, softer or lower a vowel is sung, the more it will migrate from its original version. Although modification is necessary for all voice types, the problem affects sopranos and tenors especially because they must reconcile with the higher frequencies and intensities of higher and louder tones, and a large resonating cavity is needed to avoid placing strain on the larynx.

Vowel modification (the use of acoustical vowels) is also important in the technique of formant tuning, since modifying vowels is done through making slight adjustments of the vocal tract (the resonator), which in turn changes the acoustical qualities and values of the sung vowels.

Resonance adjustments (acoustic shifts) should occur around D for all singers, although depending on the vowel modification involved, they may happen sometimes on C#. It does not depend on voice type, as acoustic shifts tend to happen in the same place within the scale regardless of the singer's voice type (and gender). Vowel charts - see below - can be followed to accomplish the acoustic shift from formant 1 to formant 2 between specific areas of the singer's range.

Good acoustic shifts are especially important for the skill of seamlessly bridging the registers, as well as for accessing pitches above speech-inflection range (i.e., head register). This shifting is subtle, and takes place gradually throughout the scale. If it is left to occur only at the pivotal registration points (passaggi) where the muscular shifts occur, there will be a noticeable difference in the tone quality and in the vowel quality, and the shift will be made more noticeable by a register break. As I emphasized in the Blending the Registers section of Good Tone Production for Singing, anticipating the registration points and making subtle adjustments to the vocal tract a few notes ahead of time will enable the singer to safely and comfortably execute register changes.